Joe Diggs

"The inspiration for (Diggs') paintings ranges from realist depictions of African American history to personal family memories, from plein-air landscapes to abstract studies all united by a celebration of texture, color, and form"

Joseph (Joe) Diggs is a practicing artist, curator, and educator with generational roots on Cape Cod. His paintings range from realist depictions of African American history and personal family memories to gestural plein-air landscapes and geometric abstractions, and they span in scale from large, wall-sized murals to small, intimate works on cardboard.

Joe Diggs' expansive artistic vision is unified by dynamic textures, perspectives, colors, and forms. Although anchored in his local Cape Cod community, Diggs' paintings are in many national and international private collections.

Joe Diggs is represented by the Berta Walker Gallery in Provincetown, MA.

-

Untitled (Brother)

Untitled (Brother) -

Untitled (Grandfather)

Untitled (Grandfather) -

Diggs Race Relations, 2015

Diggs Race Relations, 2015 -

Independence Day on the Vineyard, 2015

Independence Day on the Vineyard, 2015 -

Generations, 2020

Generations, 2020 -

In the Rearview

In the Rearview -

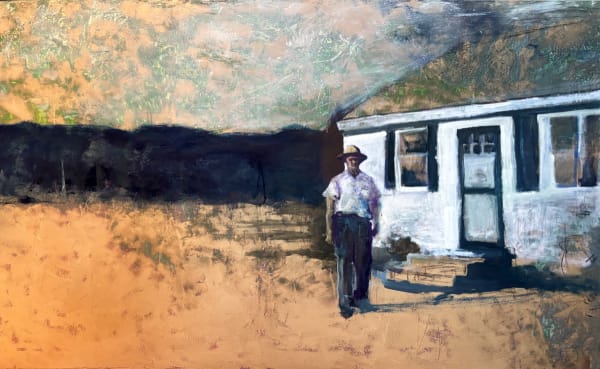

Summer Shack, 2018

Summer Shack, 2018 -

Chalk Lined Baller, 2017

Chalk Lined Baller, 2017 -

Untitled (Baller Series) , 2017

Untitled (Baller Series) , 2017 -

Good Wood, 2017

Good Wood, 2017 -

An American Tragedy, 1999

An American Tragedy, 1999 -

Misty Morning Melody, 2014

Misty Morning Melody, 2014 -

Beyond the Surface, 2014-2021

Beyond the Surface, 2014-2021 -

Micha's Pond , 2024

Micha's Pond , 2024 -

Joe’s at Sea, 2020

Joe’s at Sea, 2020 -

Summer Sensation

Summer Sensation -

Shell, 2015

Shell, 2015 -

Coastal, 2017

Coastal, 2017 -

Dreads, 2018

Dreads, 2018 -

Fisheye, 2018

Fisheye, 2018 -

Sherlock, 2018

Sherlock, 2018 -

Afternoon Nap, 2018

Afternoon Nap, 2018 -

Stormy Weather, 2018

Stormy Weather, 2018 -

Missing Kraig, 2019

Missing Kraig, 2019 -

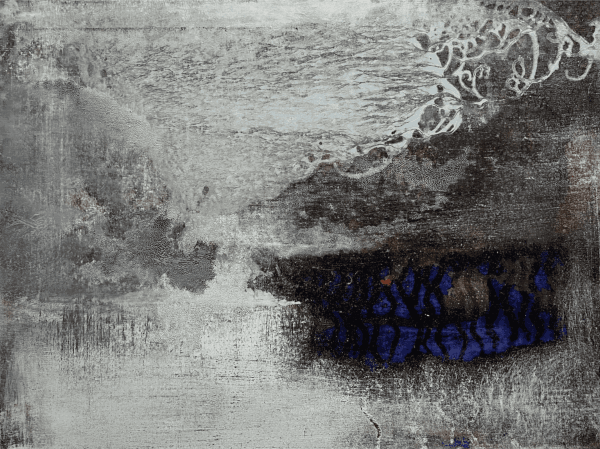

Untitled, 2019

Untitled, 2019 -

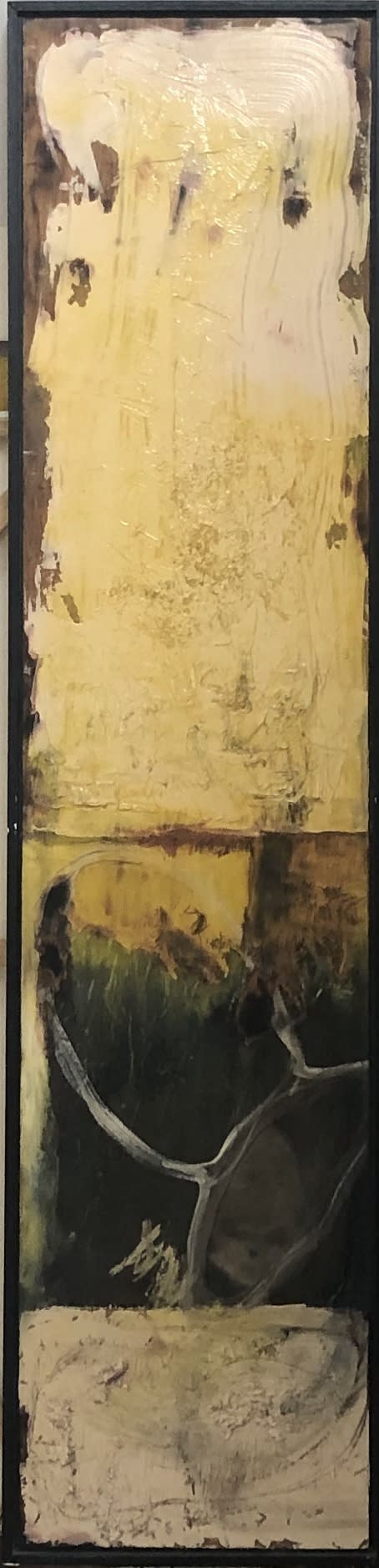

Leaving Winter, 2020-2022

Leaving Winter, 2020-2022 -

Micha's Over Blue Void, 2021

Micha's Over Blue Void, 2021 -

Cove at Micha's, 2022

Cove at Micha's, 2022 -

Shapes of Winter, 2022

Shapes of Winter, 2022 -

Golden Pond, 2023

Golden Pond, 2023 -

I Remember You, 2023

I Remember You, 2023 -

Turkey Flight, 2023

Turkey Flight, 2023 -

Spring Breaks, 2024

Spring Breaks, 2024 -

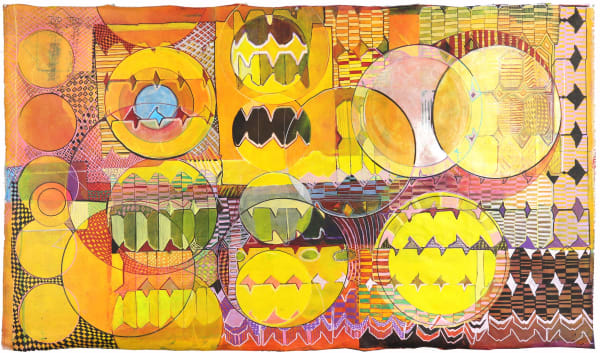

Micha's Patterns, 2023

Micha's Patterns, 2023 -

Trapped In The American Dream, 2023

Trapped In The American Dream, 2023 -

Micha's Pond with Trees, 2024

Micha's Pond with Trees, 2024 -

The Past, 2024

The Past, 2024 -

Untitled V, 2024

Untitled V, 2024 -

Another Circle, 2024

Another Circle, 2024 -

Untitled (Yellow Grapes), 2024

Untitled (Yellow Grapes), 2024 -

Untitled (Beam), 2024

Untitled (Beam), 2024 -

Untitled (Pink Curtains), 2024

Untitled (Pink Curtains), 2024 -

Untitled (Pink), 2024

Untitled (Pink), 2024 -

Untitled (separators), 2024

Untitled (separators), 2024 -

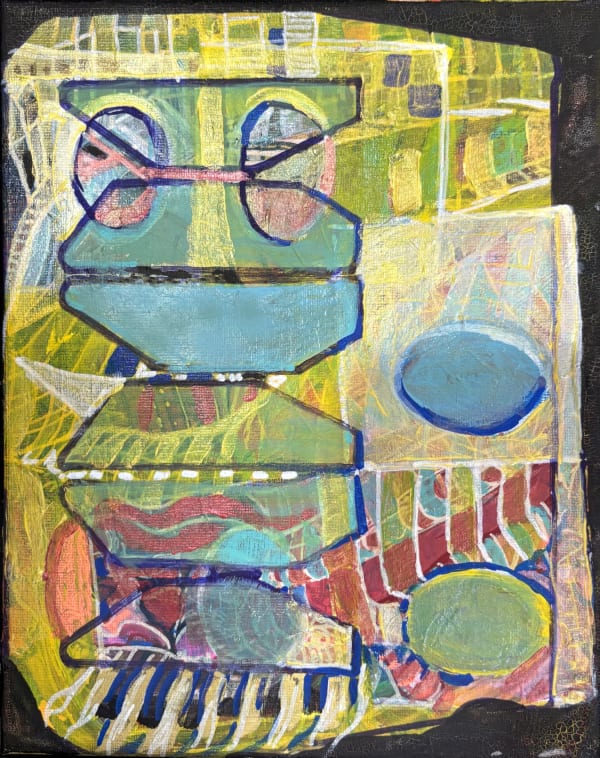

Being Boys Experience #8, 2021

Being Boys Experience #8, 2021 -

Untitled, 2024

Untitled, 2024 -

The Future, 2024

The Future, 2024 -

Transformation, 2024

Transformation, 2024 -

Under The Overpass, 2025

Under The Overpass, 2025 -

Second Right, 2025

Second Right, 2025 -

Havana, Cuba, 2025

Havana, Cuba, 2025 -

Havana Plaza, 2024

Havana Plaza, 2024

"Diggs says that one of the questions he asks himself is whether the thing he’s created is surreal or sublime. "

-Seph Rodney, All the Riches, 2025

All the Riches

by Seph Rodney

What first strikes me about the paintings of Joe Diggs is the overabundance of ideas. The phrase that comes to my mind is “an embarrassment of riches.” It’s worth asking why I might be embarrassed. Perhaps because the exquisite struggle that his paintings produce in me is that to properly to take them in, I feel I have to find a place in myself to put all this extravagant grandeur. Wandering with him through his studio and then later through his website, I realize I am too small. There isn’t room enough in my heart's house to carry all this profligate thought and perception. I’ve never felt so limited encountering an artist’s work. At his studio in Cape Cod, Massachusetts I spend hours looking and marveling at the cardboard dividers from Chinese takeout food he’s used to depict whole planetary systems cycling towards and away from their entropic doom, paper shopping bags, splayed open and painted with acrylic on each side so that each reads like pages in a massive book — flip them forward and back and enter a dream of the endless. There are also small to medium-size canvases he’s used wood trimmed by hand to frame relentlessly inventive abstract worlds, no two quite the same. Eventually, I tell him I have to stop looking. I’ve run out of bandwidth. Later, peering at the photographs I took that day, I ask myself how Diggs’s imagination became so large, a conduit for so much.

I turn to the rudimentary inventory for insight: Joseph Vincent Diggs, born of Deborah Ann Jackson, makes portraiture. Some of these works seem more concerned with documenting a certain cultural moment and saying something about how we typically see each other, such as the “Baller” series, for example “Baller Red Black & Green” (2017) which contains an x-ray of some unknown person’s lungs and a black and white photograph of a baseball summer league player, “Mr. Jones.” The work, collaged onto a plywood rectangle, suggests that our view of the figure is typically superficial, not delving like the radiograph into a body’s hidden infrastructure. Through his paintings, Diggs dives into the social and psychic plumbing of the place and people he knows. For instance, a gentle portrait of his father, Sargeant first class George Ralph Diggs in “Race Relations” (2015) depicts the elder Diggs, who began his military career in the Army as an infantryman and later became a drill sergeant and a recruiter. The actual pin his dad wore, “Diggs Race Relations”, is affixed to the painting, while the father gazes out with a resigned expression. The portrait is about more than his father; it captures a moment in the historical development of our collective understanding of and experience with race, somewhere north of “colored” and “negro,” but south of “African American” when Black people were still considered fundamentally alien to the popular idea of “American.” Diggs never entirely forgets this history and his position as a Black man in it, but at times, he leaves this aside to touch other tender places in himself.

Diggs’ portrait of his older brother, Craig Wayne Diggs, “I Dare You “holding two sections of watermelon, one in each hand, and wearing red swim trunks and sandals with a white shirt over his shoulders. He may be weighing the slices, deciding which one to devour and which to share. This is the person who initially spurred Diggs to get into art. As he attests:

I started making art, really, in high school. My brother was working on trying to be an artist, and he’s three years older than me. He was my idol, so I just followed him around. I did everything he did. I didn't have any personality. So, I just hung out ... I’m a middle child, so, you know, little issues there.

Then, at a certain point in high school, Diggs begins to acknowledge (with the help of several teachers) that something in him was good and unique, and competition with his brother showed him the way:

I was trying to beat my brother on because, you know, he just whooped my ass on everything. So, it was like, I got to beat you with something, and I just wanted to be better than him.

Craig Diggs died in a car collision at 19, and then the artist became unmoored for a time. But the place he had come to in that striving with his brother gave him a sense of himself that would not fade or falter.

Joe Diggs makes landscapes. Consider “Cove at Micha's,” (2022) with a brooding dark corner of the lake contending with the mystery of the mushy background of green forest, while in the middle-distance tree limbs cavort with lighter green swirls and dashes as if the place is not wholly natural, not entirely imaginative but a collaboration between the painter and the perceived world. An oil on linen piece “Untitled” form 2019 is more mysterious, in a primarily black and white landscape with water and bare winter trees visible, there are also masses of shrouded bodies that seem like black, white and golden ghosts, settled on the periphery of the water, waiting for their chance to make themselves more fully known.

Yes. At some point, these unsettled phantoms were representative of Joe Diggs, and then later, not, when he grasped that he had much to process growing up in a military family and coming of age in a hybrid neighborhood where oligarchs live alongside people from Cape Verde along with other Black people. Part of his story is also spending 15 years of his working life as a flight attendant. All the contrasts and inklings of worlds he’s inhabited and worlds just glimpsed come out in his paintings.

The abstract paintings are marvels — every one. It’s difficult to describe what he’s doing in these paintings because that never stops changing. I see an extended family of art historical ancestors that, though related, never read as produced by a mentor-pupil relationship. I see Hundertwasser, and Jack Whitten, Frank Bowling and Gerhard Richter. I see Helen Frankenthaler and Minor White. He tells me that he refused to pay attention to Ernie Barnes, Jean Michel Basquiat, and John Biggers because he felt their influence would be too heavy on him. Time has ratified his choice to stay within himself; he is a painter who can, at will, change his game. “Brown Paper Bag Series No. 1” (2024) shows his facility using a colorful grid to overlay a scene of organic, tubular growth meeting a cityscape containing places of habitation. Yet as I describe one painting, I know I’ve only described one planet within an entire system of swirling galaxies with undying suns, moons, and stars.

Diggs has also made work for a “Boys Being Boys” project in which he was teaching painting to incarcerated youth in a Division of Youth Services Detention Center Program at Nickerson State Park in Brewster, MA, from 2015 to 2024. Additionally, he created Project 23 with Rick and Linda Sharp to locate and document people who had been part of a Headstart program in Providence, Rhode Island, in the 1970s.

All these concerns and stylistic variants come together in his history paintings. A powerful example is “Independence Day on the Vineyard” (2015). The painting documents a visit to Martha’s Vineyard on the Independence Day holiday. The overall color scheme of red, white, and blue marks the image as one that contends with America’s past. As he tells me, Diggs and a friend, Dino Smith, brought Smith’s grandson to the Vineyard to see where African-Americans could first buy homes in the community. They sunbathed and rubbed the clay they found in the ground on their skins instead of sunblock. The boy is partly hidden, protected by the older men from the gruesome aspects of the nation’s history, including what are meant to be chalk outlined parts of James Byrd Jr’s body, indicated on the right quadrant of the canvas. Byrd Jr. was dragged to death along a three-mile stretch of asphalt road in Jasper, Texas, in 1998, chained by his ankles to a pickup truck driven by three men, two of whom were avowed white supremacists. Here we can see the combination of portraiture, a small glimpse of landscape, the abstraction that’s meant to allude to records of a murder, and that lush blend of colors that make it seem as if the entire composition had emerged from a fever dream.

Diggs says that one of the questions he asks himself is whether the thing he’s created is surreal or sublime. This sounds like his way of asking whether he is placing an overlay on a lived experience (thus creating a surreal thing, literally upon the real), or crafting an experience that abandons the everyday, travels to a place where the viewer has left earthly substance behind, as when ice sublimes away into vapor. His painting is about both motions, toward and away, always plucking at my hands, always testing and probing, seeing how much more I can hold.

SR

-

JOE DIGGS | Worlds Just Glimpsed

BERTA WALKER GALLERY 25 Jul - 17 Aug 2025Honored as Artist of the Year by The Arts Foundation of Cape Cod, Joe Diggs is being presented in two major exhibitions this summer: Evolving Circles , Provincetown Art Association...Read more -

CORRUGATED

Art About Cardboard · Opus 40 · New York 18 Jul - 7 Sep 2025CORRUGATED , a group show featuring work by Michael Ballou, Mara Clawson, Joe Diggs, Adrian Frost, Wendy Klemperer. Harvey Klimowicz. Ian Laughlin, Lowell Miller. Susanna Ronner and Christy Rupp opens...Read more